AI in Law and Legal Practice

AI in Law and Legal Practice

Originally Published: https://www.techemergence.com/ai-in-law-legal-practice-current-applications/

Last updated on by Edgar Alan Rayo

A Comprehensive View of 35 Current Applications

The growing interest in applying AI in law is said to be slowly transforming the profession and closing in on the work of paralegals, legal researchers and litigators.

In this article, we’ll discuss the different ways in which AI is currently applied in the legal profession and how technology providers are trying to streamline work processes. We break down AI’s current legal applications into the followingcategories of applications:

- Helping lawyers perform due diligence and research

- Providing additional insights and “shortcuts” through analytics

- Automating creative processes (including some writing) in legal work

Because of the breadth of our research (and hence the length of this article), we encourage readers to feel free to skip ahead to the applications areas of greatest interest for them.

We’ll conclude this article with some thoughts on AI’s promise and limitations across the legal industry.

Current developments in AI in legal practice come in various applications. Richard Susskind, one of the UK’s most respected thinkers at the intersection of legal and technology, believes that this trend will continue to grow in the coming years.

Susskind opines, “AI and other technologies are enabling machines to take on many of the tasks that many used to think required human lawyers and that’s not plateauing. It seems to be happening at quite a rate.” The developments, according to Susskind, will eventually warm up by 2020.

AI in Law: Current Applications – Insights Up Front

Based on our assessment of the companies and offerings in the legal field, current applications of AI appear to fall in six major categories:

- Due diligence – Litigators perform due diligence with the help of AI tools to uncover background information. We’ve decided to include contract review, legal research and electronic discovery in this section.

- Prediction technology – An AI software generates results that forecast litigation outcome.

- Legal analytics – Lawyers can use data points from past case law, win/loss rates and a judge’s history to be used for trends and patterns.

- Document automation – Law firms use software templates to create filled out documents based on data input.

- Intellectual property – AI tools guide lawyers in analyzing large IP portfolios and drawing insights from the content.

- Electronic billing – Lawyers’ billable hours are computed automatically.

Next, we’ll explore the major areas of current AI applications in law, individually and in depth:

(Bear in mind that the categories above and are somewhat arbitrary. We’ve done our best to place companies into the category that best represents their product offering, but it’s important to note that there is overlap on many of the groupings we’ve chosen.)

Due Diligence

One of the primary tasks that lawyers perform on behalf of their clients the confirmation of facts and figures, and thoroughly assessing a legal situation. This due diligence process is required for intelligently advising clients on what their options are, and what actions they should take.

While extensive due diligence can positively impact long-term shareholder returns (according to a study by the City University of London), the process can also be very time-consuming and tedious. Lawyers need to conduct a comprehensive investigation for meaningful results. As such, lawyers are also prone to mistakes and inaccuracy when doing spot checks.

Kira Systems

Noah Waisberg, a former M&A lawyer who founded the software company Kira Systems, thinks that due diligence errors by junior lawyers often occur for a number of reasons. These include working very late at night or on the eve of a weekend, forgetting to perform due diligence before the end of the work week, and failing to act on it when a deal structure is completely revised.

He adds, “Many associates are in a certain negative mood about the efficacy of manual due diligence. Lawyers, being human, get tired and cranky, with unfortunate implications for voluminous due diligence in M&A.”

Kira Systems asserts that its software is capable of performing a more accurate due diligence contract review by searching, highlighting, and extracting relevant content for analysis. Other team members who need to perform multiple reviews of the content can search for the extracted information with links to the original source using the software. The company claims that its system can complete the task up to 40 percent faster when using it for the first time, and up to 90 percent for those with more experience.

LEVERTON

LEVERTON, an offshoot of the German Institute for Artificial Intelligence, also uses AI to extract relevant data, manage documents and compile leases in real estate transactions. The cloud-based tool is said to be capable of reading contracts at high speeds in 20 languages.

In 2015, IT firm Atos sought the help of real estate firm Colliers International, which used LEVERTON in performing due diligence of a company that the former was about to acquire. Through the use of LEVERSON’s AI, information such as payable rent, maintenance costs and expiration dates were extracted from thousands of documents and then organized on a spreadsheet.

In the video below, LEVERTON CEO Emilio Matthaei explains how their technology is able to transform unstructured documents into useful data similar to what Colliers International accomplished.

eBrevia

However, lawyers can be burdened by reviewing multiple contracts and they may miss important edits that result to legal issues later on. This is the same problem that Ned Gannon and Adam Nguyen, co-founders of eBrevia, experienced when they were still working as junior associates. They built a startup in partnership with Columbia University with the intention of shortening the document review process.

eBrevia claims to use natural language processing and machine learning to extract relevant textual data from legal contracts and other documents to guide lawyers in analysis, due diligence and lease abstraction. A lawyer would have to customize the type of information that need to be extracted from scanned documents, and the software will then convert it to searchable text. The software will summarize the extracted documents into a report that can be shared and downloaded in different formats.

Here’s a quick introduction on how eBrevia captures content and displays relevant information to users.

Another short demo presentation on the UI was made available online by the ABA Journal (no audio accompanies the video however).

On its website, eBrevia claims that it can analyze more than 50 documents in less than a minute, 10 percent more accurate than a manual review process. The company also offers bespoke solutions by training its software to customize specific requirements of firms that require thousands of documents for rapid review. Baker McKenzie rolled out the software in 11 offices in Asia, Europe and North America in August 2017. The financial impact of this tech innovation in the law firm, however, is still unknown as the company has yet to release its findings.

JPMorgan

Other organizations such as JPMorgan in June 2016 have tapped AI by developing in-house legal technology tools. JP Morgan claims that their program, named COIN (short for Contract Intelligence), extracts 150 attributes from 12,000 commercial credit agreements and contracts in only a few seconds.

This is equivalent to 36,000 hours of legal work by its lawyers and loan officers according to the company. COIN was developed after the bank noticed an annual average of 12,000 new wholesale contracts with blatant errors.

ThoughtRiver

Other AI industry players include ThoughtRiver, which handles contracts, portfolio reviews and investigations for improved risk management. Its Fathom Contextual Interpretation Engine was developed together with machine learning expertsauthorities at Cambridge University.

The company states that it designed the product to automate summaries of high-volume contract reviews. While users users read content extracts, they can also read the meanings of clauses provided by the AI. The system is also said to be capable of flagging risky contracts automatically. The company provides a brief tour of their product in the 3-minute video below, including a detailed look at the user interface and basic functions of the software:

LawGeex

LawGeex claims that its software validates contracts if they are within predefined policies. If they fail to meet the standards, then the AI provides suggestions for editing and approval. It does this by combining machine learning, text analytics, statistical benchmarks and legal knowledge by lawyers according to the company.

In this video, LawGeex CEO Noory Bechor further explains how his product can cater to legal services.

The company also claims that with their tool, law firms can cut costs by 90 percent and reduce contract review and approval time by 80 percent (though these numbers don’t seem to be coupled with any case studies). The firm lists Deloitte and Sears among some of its current customers.

Legal Robot

On the other hand, Legal Robot, a San Francisco-based AI company, currently offers Contract Analytics, its answer to the growing contract review software market. Currently in beta, the company states that its software is capable of changing legal content into numeric form and raising issues on the document through machine learning and AI.

A video presenting how the software works states that it builds a legal language model from thousands of documents. This knowledge is used to score the contract based on language complexity, legal phrasing and enforceability. With the issues flagged by the software, it then provides suggestions on improving the contract’s compliance, consistency and readability by evaluating it on best practices, risk factors and differences in jurisdiction.

Ross Intelligence

Every lawsuit and court case requires diligent legal research. However, the amount of links to open, cases to read and information to note, can overwhelm lawyers who have limited time doing research. Lawyers can take advantage of the natural language search capability of the ROSS Intelligence software by asking questions, and receiving information such as recommended readings, related case law and secondary resources.

BakerHostetler, in what seemed like a break in tradition, employed ROSS in its bankruptcy department, 100 years after the law firm’s founding. The law firm’s chairman, Steven Kestner, explained in an interview that they decided to employ the software to work on 27 terabytes of data. A Forbes report describes ROSS’ function in the law firm’s operations: “ROSS will be able to quickly respond to questions after searching through billions of documents.

The company claims that lawyers can ask ROSS questions in plain English such as “what is the Freedom of Information Act?” and the software will respond with references and citations. Like most machine learning systems, ROSS purportedly improves with use.

Casetext

On the other hand, Casetext’s CARA claims to allow lawyers to forecast an opposing counsel’s arguments by finding opinions that were previously used by lawyers. Users can also detect cases that have been negatively treated and flagged as something that lawyers may deem unreliable.

Here is a demonstration on the functionalities of the software made by Casetext.

Casetext claims large law firms such as DLA Piper and Ogletree Deakins as its clients.

Other Assorted Applications

Other software products also combine machine learning and legal analysis to assist lawyers with legal research but with limited coverage. For example:

Loom features win/loss rates and judge ruling information but only for civil cases in select Canadian provinces. In an interview with Stanford Law School, Mona Datt (co-founder of Loom Analytics) elaborates:

“Instead of performing open text searches looking for personal injury precedents, a lawyer could use Loom’s system to see all personal injury decisions that were published in a given time span and then break them down by outcome.

Instead of combing through individual decisions looking for ones written by a particular judge, Loom’s system can show all decisions authored by that particular judge and provide an at-a-glance snapshot of their ruling history. In short, we’re providing quantitative metrics on Canadian case law.”

Judicata, on the other hand, only serves California state law as of this writing. Its software, Clerk, is said to be capable of reading and analyzing legal briefs. It also evaluates their pros and cons and then assigns a score for each brief based on arguments, drafting and context.

The recommendations intended to reduce content mistakes are listed as part of the action items for the user. In the company’s blog, Product Manager Beth Hoover explains, “Clerk helps reduce these errors by identifying the quotations in a brief and cross checking them against the cited case to ensure the text is identical and the page numbers are correct.”

Potential Bias Concerns

In a recent paper by Susan Nevelow Mart of the University of Colorado Law School tested if online legal case databases would return the same relevant search results. She found out that engineers who design these search algorithms for case databases such as Casetext, Fastcase, Google Scholar, Lexis Advance, Ravel, and Westlaw have biases on what would be a relevant case that their respective algorithms will show to the user.

For example, newer databases such as Fastcase and Google Scholar have generated less relevant search results compared to older databases such as Westlaw and Lexis. Mart argues that search algorithms should be able to generate redundant results on whatever legal online database is used since lawyers need only the most relevant cases. However, because these engineers have biases and assumptions when developing their algorithms, users are recommended to use multiple databases in order to find out the cases that fit their needs.

By no means does a single paper (or a dozen papers) imply that legal AI tools shouldn’t be used, but rather that their pros and cons are yet to be weighed out thoroughly. Bias is by no means specific to the legal field, as machine learning systems are always influenced by the data that they’re trained on.

Readers with an interest in AI bias and the ethical considerations of discrimination by machines may benefit from reading our recent article in collaboration with the IEEE: Should Business Leaders Care About AI Ethics?

Everlaw

There has been a growth in the number of e-discovery product manufacturers that harness AI and machine learning. Everlaw uses its predictive coding feature to create prediction models based on at least 300 documents that were classified before as relevant or irrelevant by the user.

The AI looks into the contents and metadata and uses such information to classify other documents. The company claims that the prediction model’s results can help users easily identify which documents are most relevant. It also recommends actions on the part of the user on how to improve the software’s predictive accuracy of the model.

You chan check a demonstration of Everlaw’s Prediction Technology feature in this video:

DISCO

DISCO claims to deliver faster results using its cloud technology for document search on large data volumes. Similar to Everlaw, it also employs prediction technology to suggest which documents are most likely to be relevant or irrelevant to the user.

The AI works by assigning scores on tags (on a scale of -100 to +100) in order to improve its prediction results. The software displays its search results with each document’s score and suggests which material is most likely useful for the reader. In the promotional video below, Dr. Alan Lockett (DISCO’s Head of Data Science) explains the company’s technology in simple terms:

Catalyst

Denver-based Catalyst markets its Automated Redaction product to help lawyers and legal reviewers remove sensitive and confidential information on documents. “Manual redaction”, as the company claims, is cumbersome considering the amount of time that a reviewer spends on locating content on a digital document and then applying black boxes on these statements.

Their tool allows users to convert a document to digital format and then perform multiple sets of redactions for a single document by searching for a word or phrase. Users can also set patterns such as social security numbers on the software to be redacted. An overview of the Automated Redaction feature for e-Discovery introduces its uses.

Exterro

Exterro’s WhatSun claims to combine the functions of a project management software with the capabilities of performing e-Discovery. In other words, users can perform their legal research and then collaborate with others using the software.

According to one of Exterro’s law firm clients, they were able to cut down on redundant workers from 100 lawyers down to 5 when they started to employ the system. The software was able to perform the e-Discovery tasks of the lawyers at a 95 percent cost savings according to the law firm. The company claims AOL, Microsoft, and Target among its marquee customers.

Brainspace Discovery

Brainspace Discovery clusters and sorts documents to match closely to a user’s document search. When finding documents, the AI employs concept search (searching for documents that are similar in concept but not necessarily in words or phrases), term or phrase extension (instructing the software to remove terms incorrectly associated with the results), and classification (specifying another category to refine the search). The company claims that by combining these three features, the software can better deliver document search results closer to a user’s needs.

Other AI-powered contract review platforms that cater to due diligence for legal professionals include:

- iManage’s RAVN whose M&A Due Diligence Robot is designed for M&A documents to automate the review process and extract data from cluster sets;

- LitIQ, which capitalizes on computational linguistics technology to reduce contract-related disputes (Gary Sangha, founder of LitIQ shares his thoughts on the relationship of machine learning and law in this interview);

- LegalSifter, which claims to cut time and financial costs through its AI software that looks for specific concepts in documents such as general terms and conditions and confidentiality agreements;

- Seal, whose software is used by Dropbox, PayPal and Experian, was able to reduce the time spent to 48 hours from 255 days by a utility company by searching for thousands of contracts with specific clauses according to their case study; and

- Luminance, which claims to be the only tool that searches and ranks unusual and anomalous documents and clauses for lawyers.

While there has been a growth in the use of e-Discovery tools, its application has become a public issue in states such as California. In 2015, the State Bar released an amended Proposed Formal Opinion, requiring lawyers to have a decent knowledge on the to use the e-Discovery system or they will warrant discipline after being proven to have committed intentional or reckless acts. The State Bar also suggests that if a lawyer is incompetent on the facility, he should learn the skill, hire someone who’s knowledgeable, or just simply decline representation.

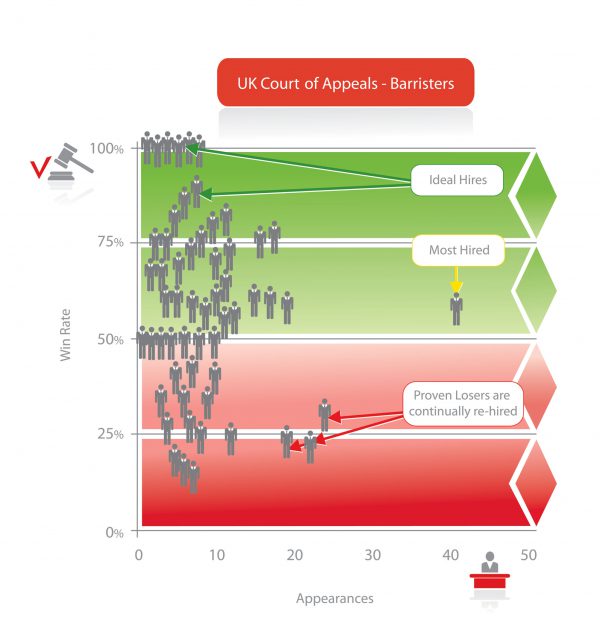

Prediction Technology

In 2004, a group of professors from Washington University tested their algorithm’s accuracy in forecasting Supreme Court decisions on all 628 argued cases in 2002. They compared their algorithm’s results against a team of experts’ findings. The statistical model by the researchers proved to be a better predictor by correctly forecasting 75 percent of the outcomes compared to the expert’s 59 percent accuracy.

Expanding the coverage from 1816 to 2015, Prof. Daniel Katz of Michigan State University and his two colleagues achieved a 70.2 percent accuracy on case outcomes of the Supreme Court in their 2017 study. Similarly, Nikolaos Aletras of University College London and his team used machine learning to analyze case text of the European Court of Human Rights and reported a 79 percent accuracy on their outcome prediction.

Prof. Daniel Kantz, in his 2012 paper, stated, “Quantitative legal prediction already plays a significant role in certain practice areas and this role is likely to increase as greater access to appropriate legal data becomes available.”

Intraspexion

Indeed, several AI companies have ventured into this field such as Intraspexion, which has patented software systems that claim to present early warning signs to lawyers when the AI tool detects threats of litigation.

The system works by searching for high-risk documents and displays them according to the level of risk that the AI has determined. When a user clicks on a document, risk terms as identified by subject matter experts through the algorithm are highlighted. According to the company, users can which documents put them at risk for litigation when they use the software.

Ravel Law

Another tool, Ravel Law, is said to be able to identify outcomes based on relevant case law, judge rulings and referenced language from more than 400 courts. The product’s Judge Dashboard feature contains cases, citations, circuits and decisions of a specific judge that is said to aid lawyers in understanding how judge is likely to rule on a case.

The firm’s CEO, Daniel Lewis, affirms such claim in this interview when he explained that the Ravel Law can aid in litigation strategy by providing information on how judges make decisions.

Lex Machina

Lex Machina’s Legal Analytics Platform has a variety of features that are said to assist lawyers in their legal strategy. For example, the Timing Analytics feature uses AI to predict an estimated time when a case goes to trial before a specific judge.

The Party Group Editor, on the other hand, allows users to select lawyers and analyze their experience before a judge or a court and the number of lawsuits they were involved in before, among others. In the video below, the product’s user interface is featured and sample analytics results are presented:

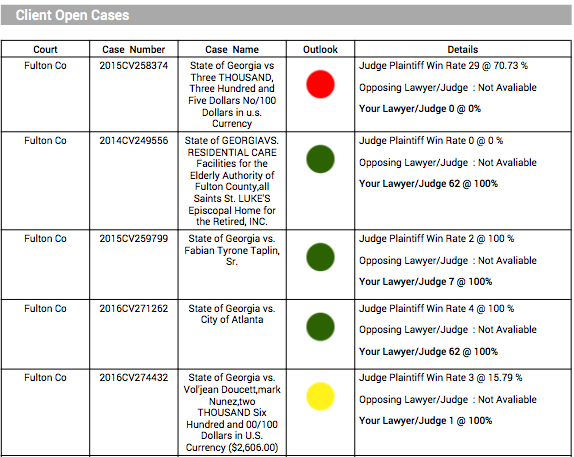

Premonition

Finally, Premonition, which claims to be the world’s largest litigation database, asserts to have invented the concept of predicting a lawyer’s success by analyzing his win rate, case duration and type, and his pairing with a judge at an accuracy of30.7 percent average case outcome. According to the company, the product can also aid in looking at different cases and how long they’re going to take for each attorney.

But similar to any analytics platform, AI tools that deal with predictive technology need a lot of data in the form of case documents to fully work according to Kantz. In an article, the model is described as “exceptionally complicated.” That’s because it needs almost 95 variables (with almost precise values up to four decimal places) supported by almost 4,000 randomized decision trees to predict a judge’s vote.Kratz admits that a database that will fully support his product is still not readily available except for a few ones that charge access fees to obtain data.

Legal Analytics

Case documents and docket entries provide supplementary insights during litigation by lawyers. Current AI tools claim that today’s software products are able to extract key data points from these documents to support arguments.

Lex Machina

Hogan Lovells litigation attorney Dr. Chris Mammen, uses Lex Machina’s Legal Analytics software to find out “who is the plaintiff, who is their counsel, who have they represented, and who else have they sued.”

The software generates data that can be used to analyze an opposing counsel’s likelihood of winning or losing a case. He claims to save time through the analytics results when creating a narrative. “You send an email to the research department, get first results, iterate the process – that usually takes a day or more.”

Intellectual property lawyer Huong Nguyen also used the software when she represented a generic pharma company. Using the Legal Analytics tool,, she found out that the judge’s history of ruling cases tend to favor cases like hers. Both parties settled in the end, which was a better resolution according to Nguyen.

Ravel Law

The data can also be used in pitching a law firm’s services to potential clients by providing intelligence on the opposing counsel, generating values on probability of winning the case and identifying litigation trends to use in their marketing campaigns.

Apart from prediction technology, Ravel Law’s software also claims to provide lawyers with judges’ data on cases, circuits and ruling on their dashboard, which can be used in landing new clients. Currently, the company is bolstering their data minefield by working with Harvard Law School in digitizing the faculty’s US case law library to be made available on its tech platform.

Settlement Analytics

It must be noted that legal analytics still has its limitations. Robert Parnell, CEO of SettlementAnalytics, explains in his paper that there is uncertainty in producing results with high level of accuracy with this kind of technology. This comes in very small sample sizes after filtering, cognitive biases, the tendency to interpret random trends as valid patterns, and having a lot of data noise.

Parnell opines, “Overall, the quantitative analysis of legal data is much more challenging and error-prone than is generally acknowledged. Although it is appealing to view data analytics as a simple tool, there is a danger of neglecting the science in what is basically data science. The consequences of this can be harmful to decision making.”

Document Automation

A McKinsey & Company report estimates that knowledge work automation will most likely be one of the top disruptors in the global economy.

A screen shot from McKinsey’s report, cited above. See the orange bar to the right of “2. Automation of knowledge work”

Some law firms are also beginning to adapt such technology by drafting documents through automated software. Many such software companies claim that the final document, which could take days by manual human drafting, is generated in a matter of minutes.

PerfectNDA

Neota Logic System claims that its software PerfectNDA shortens the nondisclosure agreement (NDA) process by offering templates selected by AI according to a user’s scenario. The user answers questions and a pre-filled template is then generated. In addition, the software also features document filing and integrated e-signatures to streamline related manual processes involved in NDA drafting.

Intellectual Property

Securing patents, copyrights and trademarks is often best left to a lawyer’s expertise. However, the entire patent application process can be long and arduous. Traditional trademark and patent search, for example, involves looking into hundreds, if not thousands, of results through manual research. This takes so much time, which is ironic considering that patent applications are time-sensitive.

According to US patent attorney Patrick Richards, “You only have one year from the first time the invention is publicly disclosed [i.e. sold] to file a patent application; if as a business owner you launched a product within the last year, you need to talk to a patent attorney right away to make sure it is protected.”

TrademarkNow

TrademarkNow is a company taking on some of the manual knowledge work of intellectual property application with AI. It uses a complex algorithm that is said to shorten weeklong searches for patents, registered products and trademark using the Trademark Clearance platform, which returns search results in less than 15 seconds according to the company’s claims.

The system analyzes the results and ranks them according to relevance to the user as identified by the algorithm. As this many e-discovery applications, the solution promises efficiency of spent attention for legal teams.

ANAQUA Studio

The cloud-based ANAQUA Studio, on the other hand, is specifically designed for drafting patents and prosecution. The company’s data sheet states that it’s the first patent application-drafting tool for lawyers that save four hours on provisional patent application and 20 hours and non-provisional types. The system is said to be able to detect document errors, circular claim references and formatting defects aside from automatically generating literal claims support.

SmartShell

Seattle-based TurboPatent released SmartShell to support paralegals performing document reviews, drafting, formatting and identifying issues on patent applications. The software uses AI and natural language processing to assist in creating legal claims.

In a case study listed on TurboPatent’s website, two paralegals from the Pacific Patent Group used the software to perform document retrieval, bibliographic data research, examiner remarks review and rejection issues discovery. TurboPatent claims that Pacific’s paralegals were 500-800% more productive in their tasks when using SmartShell (thought the case study isn’t clear what exact tasks were relevant for the software, and which weren’t – we can assume that many paralegal tasks aren’t currently improvable with AI).

An brief overview of how the product’s functions and value proposition can be seen in the 1-minute video below:

Electronic Billing

Electronic Billing platforms provide an alternative to paper-based invoicing with the goal of reducing disputes on line items, more accurate client adjustments, (potentially) more accurate reporting and tracking, and reduced paper costs.

Brightflag

Brightflag offers a centralized legal pricing software that automatically adjusts line-by-line items. It also allows users to centralize the invoice review so that all documents submitted are routed directly to the correct approver. In addition, the AI provides analytics features by tracking and categorizing all pricing data to determine alternative fee arrangements (AFA) and budgets.

The company claims that its average client reduces administrative costs related to payment management by 8 to 12 percent by using the platform’s assisted review feature. The company lists telecom giant Telstra and ride-hailing company Uber among its current marquee clients.

Smokeball

Smokeball’s cloud-based legal practice management tool automates the recording of time and activities by law firms. One major feature of this tool is the capability to track all activities including emails that are valid for billing. It claims to have automated more than 600,000 forms and managed over 10 million documents according to its website. The video below explains Smokeball’s software:

Unintended Consequences

But not all lawyers find this technology highly worthwhile. For example, Mark Herrmann, chief counsel at consultancy firm Aon, sees e-billing’s limitations. He states, “…automated systems that unthinkingly cut bills can lead to unintended consequences. For example, some corporate clients refuse to pay for more than ten hours of a single lawyer’s time billed in one day unless the lawyer is physically at a trial site.”

Echoing Herrman’s sentiment, Wayne Nykyforchyn, CEO of InvoicePrep, states that e-billing falls short on making judgment on its own results. “Dutifully, the software puts a flag next to all line items that contain key combinations of words, UTBMS task codes, and timekeeper roles. Is the description adequate? Was the time reasonable? Was authorization actually given? The software has no idea,” he writes. Because of this, the red flags that the software has made for possible adjustments still need to be evaluated by a reviewer.

Concluding Thoughts on AI in Law and Legal Practice

In exploring dozens of AI legal-tech companies and use-cases, there are many looming questions with respect to adoption. In other words: Which firms will use these technologies – and which AI legal-tech applications will become commonplace in the short term?

I’ll conclude this article with some thoughts about what might be a bit of a “catch 22” for AI in law and the legal profession.

The most acknowledged benefit of AI tools in legal practice seems to be improving efficiency. AI software employs algorithms that speed up document processing while detecting for errors and other issues.

This seems somewhat counterintuitive as the legal professional has long relied on “billable hours”, and it often does not behoove a lawyer to take less time in completing a task or document. For this reason, merely eliminating manual (or boring) tasks will likely not be strong enough to drive AI adoption.

Rather, the pressure to adopt AI will likely come from peer pressure. Legal firms who adopt AI and are able to move faster may be more likely to pass those savings immediately on to their clients, and firms with no ability to automate may find themselves relatively overpriced for legal services that other firms have largely automated away.

It is unclear as to how the transition to legal AI will occur. On the one hand, we might expect large law firms to drive initial adoption as they are most able to pay for robust AI-based tools and integrations. However, newer firms would be most likely be begin with a lean, automated, efficiency-driven approach, because they don’t have to deal with the massive existing overhead of larger firms.

TechEmergence CEO Daniel Faggella believe that broad adoption of AI in law may begin with an ecosystem of small, nimble legal firms will emerge – a group of firms focused from day one on maximal automation and efficiency.

These firms will likely apply AI and other software to a specific legal domain (possible wills and trusts, or patent law, or commercial real estate contract review, etc), and they’ll be able to leverage technology to garner large profit-per-employee numbers.

This won’t be done through massively high rates for their billable hours, but by charging low rates and scaling their services with automation. For example, a narrow new tech-driven legal firm focused on patent law might streamline their lead generation and sales process, and automate a huge majority (or at least a significant portion) of their services with natural language processing and AI. Faggella states:

“The emergence of these smaller firms will shock the larger legal players, who will scramble to keep their prices and services competitive – much in the same way that stodgy paper-based newspapers had to adjust to digital publishing.

By in large, they didn’t adjust. Instead, a cadre of up-and-comers ate their lunch and most of the stodgy publishers died off or clung on by their fingernails with herculean effort. It’s unclear whether a similar shift will be as fast with the legal field as it was with publishing, but the same kind of sea change seems to be underway.”

Some lawyers will argue that ‘Smart people won’t like this technology, they’ll want it done the old fashioned way.’ Indeed for some legal matters there may be little choice but to leverage human expertise, but other processes and services will be augmented heavily by AI, and the field itself will eventually have to shift.