‘Dilemmas, Decisions + Data’ – Premonition

‘Dilemmas, Decisions + Data’ – Premonition

This is a Sponsored Thought Leadership article from legal AI analytics company, Premonition, by its UK Director, Ian Dodd.

‘Facts do not cease to exist just because they are ignored.’ – Aldous Huxley

You can hardly switch on your laptop these days without somebody banging on about AI, data and how it’s all going to change your working world. Well, it all might but only if you agree with Aldous Huxley. If you don’t agree with him, you can save a lot of time by stopping reading now.

Still here? – Then I’ll begin.

The rest of this piece is about what lawyers and their clients might do about all of this stuff.

First, though, it’s important to differentiate between process automation and data analytics.

The first, which seems to be in the plans of many law firms currently, is how AI will organise contracts, order information more efficiently and, generally save time, money and, possibly, jobs. And there’s a lot of service/product suppliers in this part of the market.

Predictably, there are fewer vendors providing bespoke data analytics. That’s because this is harder to set up, requires a lot of data crawlers/scrapers, and also savvy buyers to appreciate the value of the data. They also need the breadth of strategic vision to interpret it and understand its business, social and personal implications.

Premonition is one of these vendors.

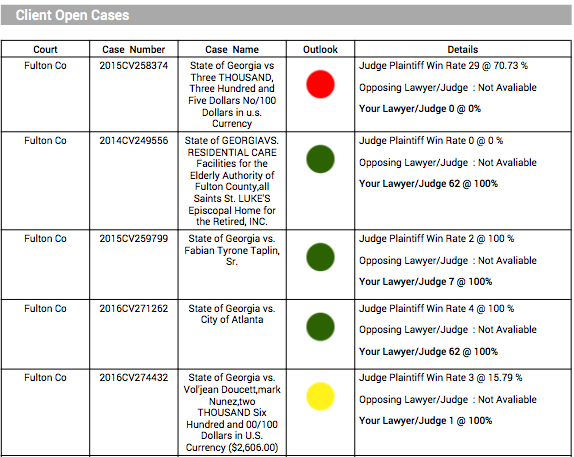

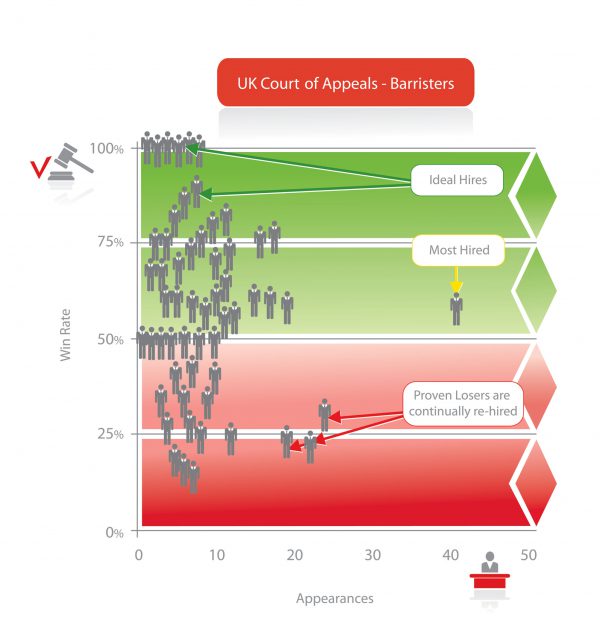

For lawyers, the use of data analytics might start with a benchmarking exercise of how they, their competitors and the barristers (or if outside the UK, the trial attorneys) they instruct, perform in the many courts that provide case details.

These will be part of the public record (and, consequently, unimpeachable), machine-readable and comprehensive with regard to the depth of detail available.

This will also be quantitative, objective and empirical and might be regarded by anyone with a penetrating eye for such things as more valuable than the costly ‘quality-by-opinion’ legal directory entries that proliferate today.

For the clients of lawyers, fully analysed court data provides comparative, hard information about the performance of those they instruct. This can reveal previously opaque and valuable facts, which along with their other selection criteria, make their job easier and more accurate. Lawyers with a record of good court performances usually provide their clients with better outcomes.

Quite apart from providing data to be used to compare and chose lawyers, the information embedded in court case records gives those with a specific business objective the power to find a wealth of data which may be meaningless to anyone but them.

Quite apart from providing data to be used to compare and chose lawyers, the information embedded in court case records gives those with a specific business objective the power to find a wealth of data which may be meaningless to anyone but them.

Imagine a specific and, possibly, injurious chemical recently introduced for everyday use by a large population of consumers. Imagine, also, an insurer who, anticipating future class actions around the effects of this chemical, can find out all about the appearance of it in world-wide litigation cases.

Imagine a property investor looking for distressed debts, wanting to have all the case details about banks suing borrowers for debt default. All they’ve got to do is specify the search fields and the machine will do the rest.

Imagine all the similar questions that every business in the world can ask about its own, very specific, activities and all the answers some data-mining can provide.

Most law firms, and their clients, have been scanning documents, storing data and collecting information for many years. There are billions of facts, sitting in servers, which might have been used only once.

The smart folk are beginning to realise the gold mine of data they have inside their own businesses. With the right help they’ll be able to collect, analyse and interpret this intellectual property, repackage it and sell it; not once, but many times to a data-hungry client base.

However, it’s going to take a fundamental change in thinking in many law firms to profit from the undoubted opportunities AI is presenting.

Stifled by tradition, hierarchy and a silo mentality many are relentlessly resisting even the efforts of the most energetic senior managers to move things on.

The Challenges of Law Firm Innovation

It seems to be wildly fashionable to have someone in a law firm, particularly in London, with the word ‘innovation’ in their title. Some are doing a good job and, actually, innovating. Many, though, seem to be tokens to modernity and are, possibly, in post because a competitor has one. Many are impossibly young and, while technologically equipped, perhaps don’t have the commercial experience to spot and exploit the business opportunities there are.

It might also be the case that those doing some really good work in big firms are blocked by the traditional partnership model and risk-averse equity partners, and that the innovation voices are crowded out by the monolithic culture that still exists.

I’m much more confident of the potential profitability of ‘innovation’ when I see one of the more mature and senior partners with the word in their title, or real support given to those who are charged with the task.

Lawyers, then, are struggling with dilemmas: all the evidence that AI will not only hasten change, but create its own unique challenges, is here.

Where to start and what to do with it might be the question. That’s where smart decision-making is needed.

The facts, in the form of data, that will guarantee success in the way AI is managed are all there. They exist, they’re just being ignored.

This article was originally published on the 21st of November 2017 from the artificiallawyer.com

- Check out our blog for more of the latest on where legal analytics is headed.