Goodbye Legal Directories, Hello Legal Analytics

Goodbye Legal Directories, Hello Legal Analytics

There’s that old saying … in the land of the blind, the one eyed man is king well, historically when it came to choosing lawyers, choosing blind was the status quo for many clients.

The market size of the US legal services sector is estimated to exceed $437 billion annually, and yet there are no agreed-upon metrics to help consumers evaluate a lawyer or law firm’s performance before making a hire. Like medicine, the practice of law is so technical it takes an expert to judge whether a lawyer is good at their job.

Enter legal directories. Here’s how one of the industry leaders, Chambers and Partners, describes the methodology it uses to create its rankings:

“We rank both lawyers and law firms based on the research of more than 170 full-time editors and researchers employed at our head office in London. We talk to lawyers and clients all the year round, conducting in-depth telephone interviews.”

At their best, then, legal directories create qualitative rankings based on the general perception of who does their job best. At their worst, legal directories are openly fraudulent. Consider this excerpt of a quote from a big firm’s Chief Marketing Officer that Chambers uses to promote its services:

“In a legal marketing world that is literally awash in gratuitous and duplicative listings, pay-for-plays, unresearched ratings, rankings and scams—over 900 at last count—there are innumerable ways for lawyers and marketing departments to waste their time and money.”

It seldom bodes well for the health of an industry when the bulk of its practitioners are literally confidence artists. Although the quote goes on to claim that Chambers is “an island of sanity” amid the debris, it is telling that even the most incorruptible legal directories are still primarily marketing collateral for the firms, with qualitative rankings based upon the self-reporting of marketers. Regardless of their methodology, the key question remains whether or not their advice actually benefits clients. Recent academic research takes a dim view, as Dr. Chris Hanretty of the University of East Anglia notes in an unambiguously titled article called “Lawyer rankings either do not matter for litigation outcomes or are redundant”:

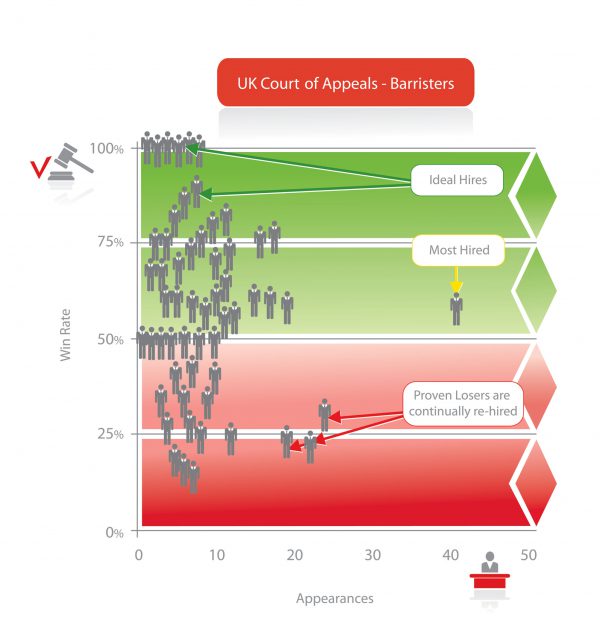

“I explore the effect upon success of having better-ranked legal representation, according to rankings of barristers published by Chambers. I find that, for a variety of model specifications, there is no significant positive effect of having better-ranked legal representation. […] Better-ranked legal representation might have a positive effect on litigation outcomes, but only if better-ranked lawyers receive cases that are substantially more difficult to win. However, if better-ranked lawyers receive substantially more difficult cases, this suggests consumers of legal representation are sophisticated enough to dispense with legal rankings.” (Emphasis added.)

If legal directories are of little real benefit to consumers, it is clear their continued existence is thanks to the conservatism of marketing departments. Law firms are stuck paying into the rankings because they fear that leaving will cede some advantage to their competitors, even if they are not completely sure anyone is actually using the directories. Is this Pascal’s Wager as marketing strategy, or the Panopticon? Choose your metaphor, but the result is the same. Dr. Hanretty’s case against Chambers is based on a quantitative analysis: that is, by looking at how often lawyers in the directories actually win in court, he can compare their rankings to their actual performance. It has long played to the directories’ advantage that, despite court records nominally being part of the public record, the sheer volume of information researchers needed to process to produce findings like Hanretty’s severely limited their scope of inquiry.

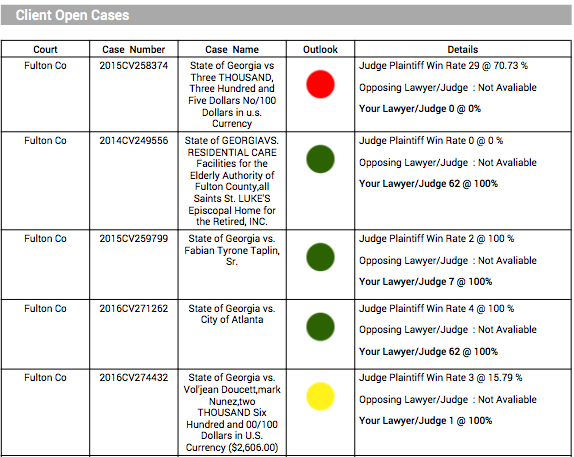

This has all changed with the advent of legal analytics (also known as Big Data). Start-ups like Premonition, Lex Machina and IBM’s ROSS AI have made it possible to query vast amounts of litigation data and legal analytics in a matter of seconds, revealing the real performance of lawyers. Premonition, a Miami-based firm which claims to have assembled the world’s largest database of court records, emphasizes the potential of what it calls perception-reality arbitrage. If most clients share the flawed conventional wisdoms embodied by the legal directories, it follows that those with access to more empirical data are well-positioned to take advantage of the gaps between that wisdom and the truth. Premonition’s research has shown that while choosing the optimal available lawyer for the circumstances of a given case (factoring in jurisdiction, case type and judge) has a 30.7% impact on a client’s chances of winning, even law firms themselves are actually quite poor at selecting the attorneys most likely to win cases. Legal directories, which are sourced from the opinions of these very firms, are an embodiment of this flawed reasoning.

Although legal AIs can be programmed to make quite accurate predictions regarding individual cases, it is at the macro level when their skill for recognizing trends over time truly shines—that is to say, when they are tasked with the very jobs legal directories purport to do. As more general counsels begin requesting performance data from law firms before hiring representation, demand for arbitrary word-of-mouth based rankings will naturally fall.

The numbers do not lie, and they spell disaster for the industry as presently constituted. It remains to be seen whether they can successfully implement performance metrics into the way they generate their rankings, or if legal directories will soon go the way of their nearest sibling: the phone book.