Understanding Your Competition

Understanding Your Competition

Written by Brian Kennel

In our last post, we focused on assessing a firm’s competitive position by reviewing planned work-life timelines, relative workload distributions, and capacity. Please see last week’s post to review that information.

The next step is to compare your firm’s ability to perform to that of your competitors. Performing this analysis requires developing an understanding of the market and a willingness to accept the objective results.

Practicing law is not war, but knowing that you are undermanned and outgunned going into a legal battle is still important. Equally important is knowing when you have a competitive advantage.

The process for determining how well suited your firm is to compete includes understanding your top competitors’ capacity, age and experience demographics, and capability. Competitor billable capacity, age, and experience demographics are easier to determine. Assessing competitor capability requires an internal evaluation of individual competitor lawyers and external insight supported by a higher level of research.

Capacity

Smart law firms restrict the use of practice area designations to those that a lawyer is either on a competitive or a market leader level. Many law firms, however, believe it is better to show the same lawyers in many practice areas, which is usually a mistake and something I will develop in a subsequent article. The point now is that when considering a competitor’s capacity level, an evaluation of each lawyer must be performed and the fringe lawyers removed from the analysis. Likewise, if your firm is employing a “more is better philosophy” for showing practice area strength then the same removal process should occur. There are several tools available for determining competitive strength, and the first one is a capacity analysis.

Competitive Capacity Analysis

Assessing the capacity in the market is straightforward but is best kept in perspective. The most difficult part is determining the capacity of lesser known competitors and fringe lawyers. This analysis only speaks to the capacity (hours to sell) of the market. It does not consider talent levels and other qualitative factors (lawyer and firm, reputation, service levels, relationship strength, and rate/cost differentials).

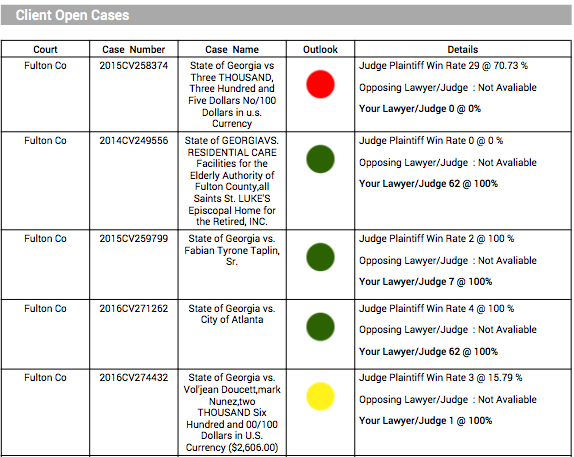

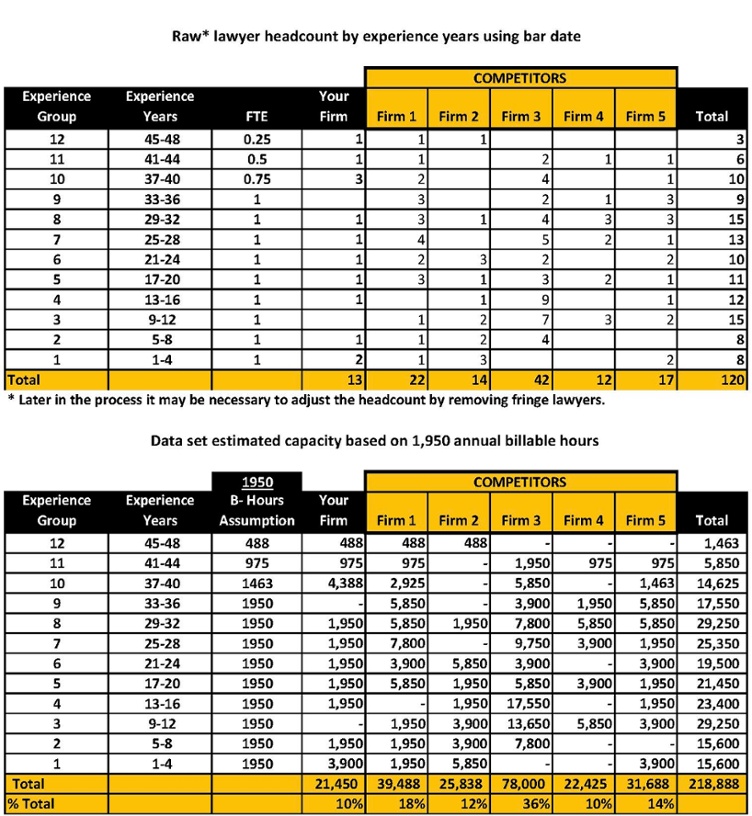

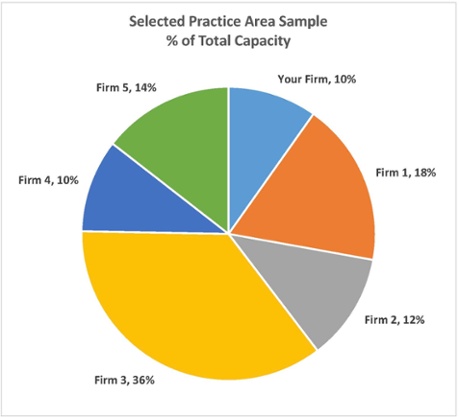

Review the data provided in Table 1 below. In this example, a firm (your firm) was interested in comparing their gross production ability (capacity) against that of its five main competitors. In the first table, all lawyers in the sample set were grouped by years of experience and assigned a corresponding FTE (full-time equivalent) assumption.

In the second table, using an assumption of 1,950 annual billable hours and the corresponding FTE assumptions, the capacity of this market segment can be calculated. The hours and FTE assumptions flexible and based on standard market practices. For example, litigation practice hours are often higher than those of non-litigation practices.

Capacity-Law-Firm-Competitor-Analysis

From this top level analysis, a firm can quickly determine how much of the market capacity they offer, and by extension the size of the market for these services. Again, this is a model. Results should be coupled with a reasonable margin for error when making conclusions about market share.

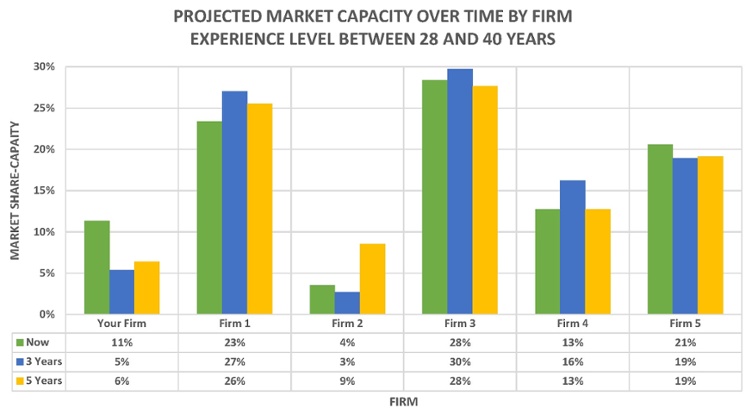

We typically create a table for these data, which provides more maximum sorting and analysis. For example, it is useful to analyze these data across each experience band. A firm may have an advantage regarding a gross capacity, but at an immediate disadvantage regarding necessary levels of experience now or into the foreseeable future. Firm 2 for example, has 12% of the market but is relatively inexperienced, having only one lawyer and a retiring senior partner, when compared to competitive firms. Depending on the quality of the more experienced lawyers in firm two, their 5-year future, however, may be bright. Viewing these data by experience slice, a firm can quickly project strength or weakness.

Graphic analysis can also be used to understand these results better. Consider the two simple charts below. A simple pie chart is effective for communicating the amount of available market capacity by the firm. The bar graph is sufficient for indicating that, assuming no course change, Your Firm will lose its competitive position to Firm 2 within five years.

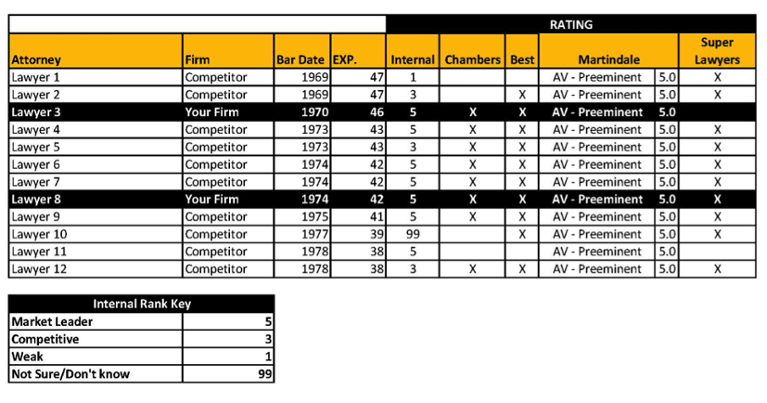

External Data

Moving beyond capacity and evaluating and assessing capability requires additional research. It is at this point we try to introduce as much external data as possible. As an example, consider the expanded data table below. Notice that we have added fields for an internal ranking, and the various forms of peer recognition. I will leave it to you to decide how much weight to give to the different rating organizations, but they do at least provide a check on internal rankings.

Additional rating information or clues may be available depending upon on practice area. Other lawyers, client and peer comments and even members of the judiciary are all potential sources for competitive ranking.

Master Competitive Data Base – Eminent Retirement Segment

The goal is to cross reference internal rankings with peer or market rankings. Practically speaking, think of that attorney that is favored with client work in spite of your perception of that lawyer’s capability. Understanding how you or your firm ranks in the market (clients, peers, judges, etc.) is the first step to improving your position.

Assessing potential opportunities and threats

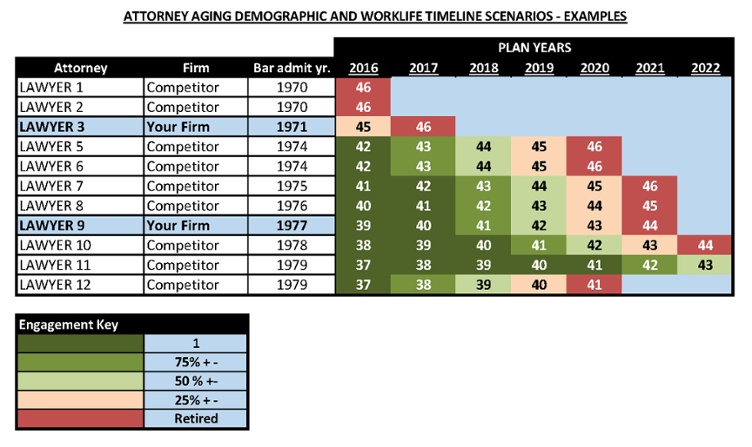

Considering individual work-life timelines for the near future may signal opportunities or threats depending upon the capability levels and competitive position of each pending retirement. For example, if your firm’s senior partners are market leaders, there may be an opening for a competitor.

Consider the following work-life timeline example:

If there were an actual example, Your Firm would be in danger of losing market share to competitors. Lawyer 3, who is ranked as a market leader, is already well into retirement. Often, partners in this situation are still the primary contact in one or more important client relationships. Cross referencing this work-life timeline with the ranking database, notice that there are five competitor lawyers who are considered market leaders. Each of these lawyers has adequate time to at least make a run for the business once Lawyer 3 retires.

Shaping conclusions based on data about real people, and how they may behave, allows for a planning process that can be specifically created to take advantage of opportunities or prepare for competitive challenges.

Advanced third-party evaluation tools

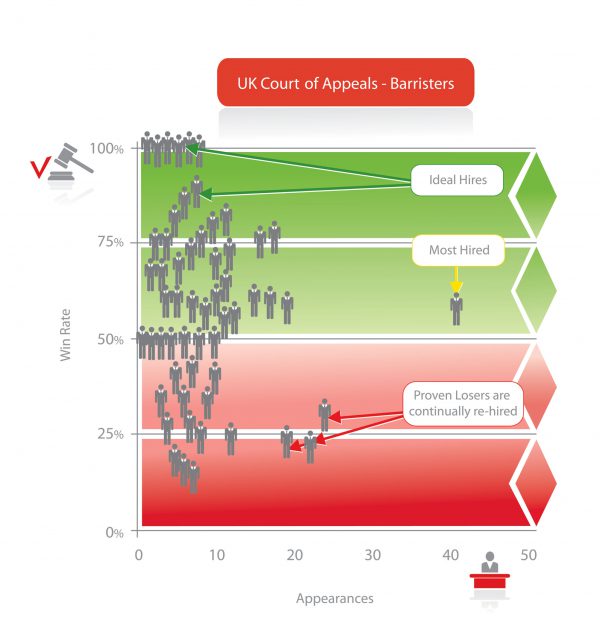

In some cases, which we believe will continue to expand, data exists to rate firm and lawyer litigation performance. Searching large amounts of publically stored court data can yield penetrating insights into how a lawyer or firm competes in court. These data points are sure to become a significant factor in the lawyer selection process. It is also important to for firm or lawyer to understand how their results compare to those of competitors

If the comparison is favorable, the firm or lawyer is operating from a position of strength. If the comparison is unfavorable, immediate improvement steps can be taken. Regardless of position, it is better to understand if your results are better or worse than those of your competitors. Clients have the capability also to evaluate firm and lawyer results using these same tools.

This type of evaluation requires a sophisticated search tool and a trained staff of programmers and analysts. The availability of these tools is becoming more widespread and available to firms on a per use basis.

ONE EXAMPLE

Over the last 12 months, I have had the opportunity to get to know Toby Unwin with Premonition. Premonition makes its living by objectively analyzing lawyer and law firm performance using available court data and their powerful search algorithms. Conceptually, this application has the potential to create real disruption in the way legal services are purchased and delivered.

The data provided by these analyses can be provocative and is often met with skepticism and disbelief. In my practice, I am advocating for more hard data analysis to ensure that a firm does not fall victim to an isolated view of the market. Competitive analysis is a process of collecting data from any available source, and I am excited about the potential of these types of tools.

Clients also can become too comfortable with their buying processes, and sometimes focus relentlessly on the cost and the length of time a particular task takes. Lawyers are often left wondering if results matter. To be fair, litigation results are often difficult to quantify, especially when high numbers of legal cases are settled during the litigation process and do not lead to an obvious win or loss.

I have also had the opportunity to consult closely with skilled litigators that point out that the easier cases settle, but the more complicated cases, especially those with a measure of clear liability, are often about mitigating an eventual award. For cases with smaller exposures, the cost of aggressively pursuing a legal matter through trial may outweigh any reduction in liability.

What about those cases, however, that do go to trial? What can we learn from the available data and is it predictive of future results? According to Unwin, the results can be startling. Premonition seeks to answer important questions about lawyer performance including:

- Is there a correlation between spending more money and result?

- Is there a correlation between billing rate and result?

- Is there a correlation between firm size and result?

- Which lawyers have the best results in a jurisdiction?

- Which lawyers have the best results for a particular matter type?

The list goes on, but the idea is to confirm the accurate perceptions of lawyer and law firm performance and to correct the wrong ones. As these data are more available and better understood by client and law firms, widespread adoption can occur, and data accuracy will improve.

Instead of focusing on all of the potential issues with the data collection, we recommend embracing what these data do tell a lawyer or a firm. Any resulting improvement, however small, may make an enormous difference in a client result.

I invite you to visit Premonition’s website and schedule a demonstration. As I am evaluating the capability and applicability of this application, I would appreciate any feedback you may have. I can be reached at [email protected].

Original Source: http://ow.ly/xIo3302P8cq